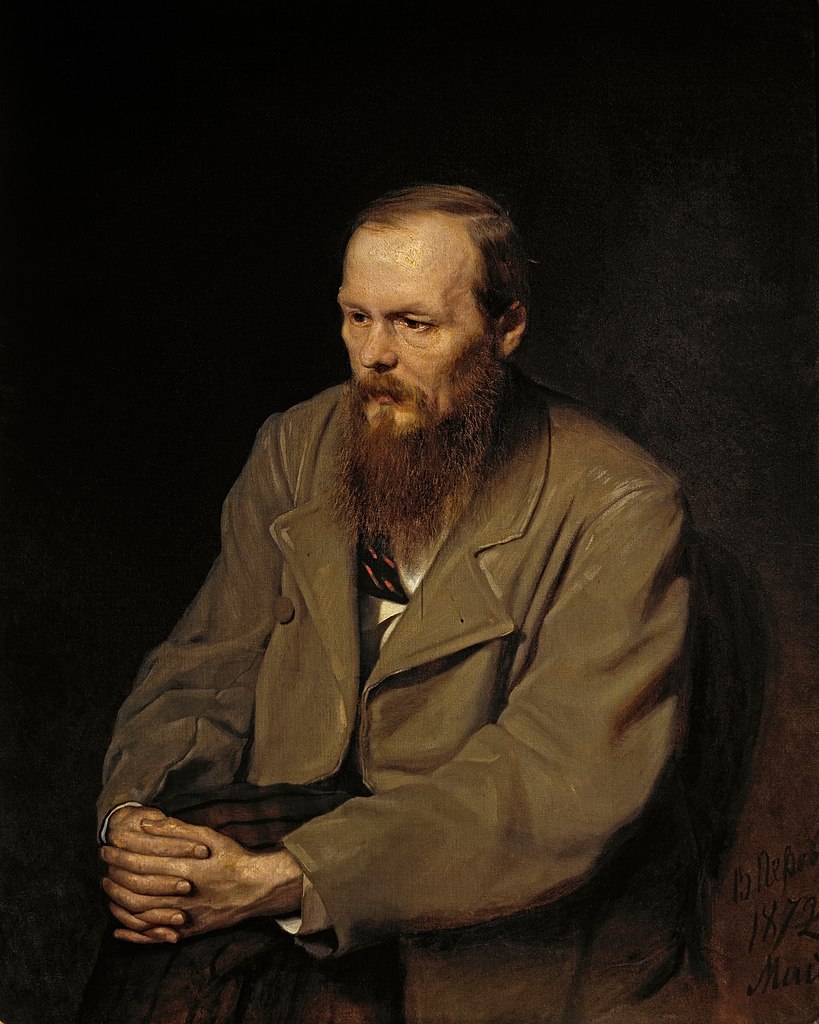

Recently, I finished reading Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel The Brothers Karamazov, a 700+ page novel about, among other things, a bizarre love triangle and a parricide. Why on earth would anyone read this massive book written in a foreign country, Russia, so long ago, in the 19th century? Aside from Dostoyevsky’s extraordinarily subtle and breathtaking insights into the human spirit, you might read Dostoyevsky to gain a better insight of how to write stellar fiction. How does Dostoyevsky build a paragraph? How does he transition between major scenes? How does he construct his sentences? How does he build a character? You don’t necessarily need a class in fiction writing to learn these things (although, that might help unpack what he is up to). For the most part, it is all there in the writing itself.

Dostoyevsky himself knew the power of imitation. In the introduction to The Brothers Karamazov, the translator Richard Pevear relates that Dostoyevsky would write pages and pages of dialogue with the goal of attempting to imitate the living word, the speech, all around him. Pevear writes,

The style of The Brothers Karamazov is based on the spoken, not the written, word. Dostoyevsky composed in voices. We know from his notebooks and letters how he gathered the phrases, mannerisms, verbal tics from which a Fyodor Pavlovich or a Smerdyakov [characters from The Brothers Karamazov] would emerge, and how he would try out these voices, writing many pages of dialogue that would never be used in the novel. (Pevear xv)

The key to Dostoyevsky’s originality and style, then, lay in his ability to listen, to watch, and to learn from others.

Indeed, you can learn a lot about how to do something simply by watching someone else. As you know, this holds true for everything from watching someone swing a golf club to observing someone flip an egg to witnessing someone pull off a great paragraph. When you read, whether fiction or non-fiction, imagine yourself as a Penn or a Teller trying to figure out how the magician, the writer, pulls off his or her trick. As the novelist Shelby Foote once related in a C-SPAN Book TV interview (entitled “In Depth with Shelby Foote”), if you want to launch into the world of novel writing, pick someone and try to imitate their style.

Imitation does not merely apply to novel writing, of course. It also appears in more mundane, worldly enterprises like sales. Those in sales can learn to practice solid, effective communication by watching how others work. In his book To Sell is Human, Daniel Pink advises the reader to pay attention to others’ sales pitches so as to better understand their techniques (177-178).

Why am I telling this to you? Because it is not always apparent to people that they can imitate another’s style to enhance their own.

Thus, as Augustine suggests in On Christian Doctrine, you have two options for learning how to become a more eloquent communicator: theory and imitation (120). Both options matter. The art of rhetoric systematizes the rules for good speaking and writing. A rhetorician might suggest that if you want to get your audience’s attention, you have several tactics at your disposal: start with a story, begin with a rhetorical question, etc. If you need to arrange your work, you can start with a problem and then provide a solution, you can arrange chronologically, etc. However, these rhetorical techniques for composing a written or spoken work, which happen to be very helpful, do not exhaust your creative possibilities for composition. You can also imitate. Pay attention to how people write essays, how they deliver presentations, etc. All these particular styles become fair game for your own communication.

So, the next time you pick up a book or listen to a Ted Talk, try to observe how the author or speaker makes it happen. How do they do it? And, perhaps more importantly, how will you do it?

In-text citations come from the following texts: Pevear, Richard. Introduction. The Brothers Karamazov. Written by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volkhonsky. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990. Pink, Daniel H. To Sell is Human. Riverhead Books, 2012. Augustine. On Christian Doctrine. Translated by D. W. Robertson, Jr. Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1958. I get commissions for purchases made through links in this post. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.